The purpose of the Circus Museum site is to make circus-related cultural heritage available to the public. The historical images featured below contain outdated and derogatory language, and the way people are depicted may be regarded as offensive. Their online availability is, however, in no way intended to offend anyone.

Human Exhibitions in the Circus Collections (1887-1957)

In the period 1875-1940, exhibiting people from Africa, Asia and the Americas was a major element of mass culture. The rise of this type of entertainment coincided with modern imperialism. Posters and photographs of human zoos reflect the European perception of non-European cultures at the time.

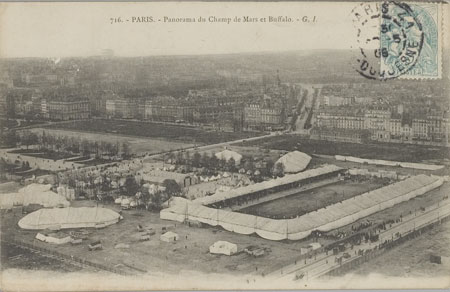

Human exhibitions were organized by the authorities as well as private individuals. The material held in the Circus Collections comprises the period 1887-1957 and concerns German entrepreneurs. They toured Western and Eastern Europe and staged shows at events venues and zoos.

The play bills, post cards and photographs reflect the Western gaze of the organizers, yet the perspective of the people who were put on display is lacking. The performers were recruited, presented and treated in several ways, ranging from coercion and exploitation to the active involvement of troupes who helped shape the shows. The wish to escape from poverty or social marginalisation might have been an incentive to participate in these tours, which lasted for months.

Hierarchy of Race

Scientists collaborated with German organizers to acquire knowledge about global cultures. The performers’ body measurements were taken, and the colour of their skin and the texture of their hair was determined on the basis of detailed schemes. These measurements and anthropological photographs continued to be a source of research for decades.

The body measurements contributed to a construction of human races, with the ‘Western race’ considered as the apex of human development. Initially, these evolutionary race theories were restricted to scientific circles, but the ethnic shows that drew millions of people helped to popularize and cement notions of racial superiority and inferiority.

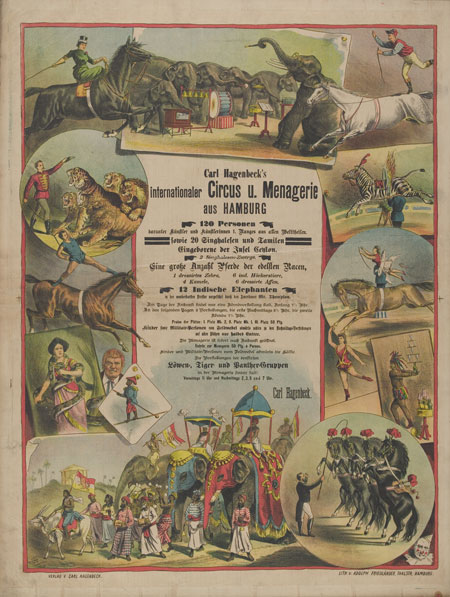

Trade in Animals

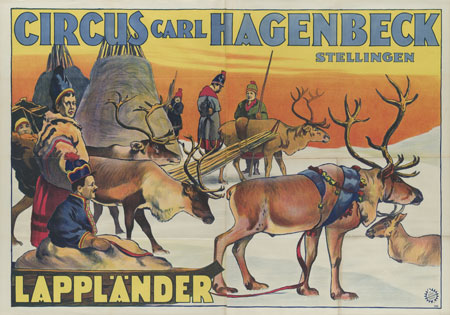

With seventy human zoos between 1875 and 1931, the German firm of Hagenbeck was a key player. Hagenbeck was also the world’s largest trader in animals. In the first shows, organized by Carl Hagenbeck (1844-1913) (TEY001015893), Sámi from Lapland demonstrated how they lived among reindeer and caught seals. The show was an immediate success, and groups of Sámi regularly returned to tour Europe. (TEY0010003416, TEY0010002576, TEY0010003354). Towards the end of the nineteenth century, almost half the programme consisted of acts with wild animals.

Somali Monopoly

The European exploration of Northeast Africa gave Hagenbeck the opportunity to expand the trade in animals. Expeditions made vast expanses of land available, where animals were hunted extensively. By capturing thousands of giraffes, antelopes, leopards and lions, the firm changed the landscape forever.

Hagenbeck’s agents employed Somali hunters, who were also recruited for the shows in Germany. In the posters, the Somali were almost invariably depicted with animals, as a ‘primitive people’ far removed from modern, industrialized European society.(TEY0010000012, TEY0010000014, TEY0010000031, TEY0010002681).

Nevertheless, the Somali also helped shape the shows. Hersi Egeh Gorseh recruited members of his community and trained them to perform in the dance and battle scenes that were staged. By appropriating the costume, songs and dances of neighbouring ethnic communities, Gorseh furthermore imbued the shows with a strong Northeast African slant. The Somali thus also doubled as Abyssinians or Eritreans. Gorseh travelled through Europe between 1885 and 1929, visiting the Netherlands with his troupe in the latter year. (TEY001008817 t/m TEY001008819, TEY001008796, TEY001008798). Two of the troupe’s members drowned while staying in Scheveningen.

Marginalisation

The Sudanese Revolt hampered the trade in animals in Northeast Africa, so that Hagenbeck turned to Sri Lanka for new hunting grounds. This way, the firm also hoped to meet the demand for elephants from American circuses.

John Hagenbeck (1866–1940) settled in Sri Lanka (Ceylon), where he managed plantations. The harvest from his tea plantations was sold in Germany as ‘Hagenbeck’s Ceylon Tea’ (TEY0010002845). He also created large-scale spectacles with Indian and Sri Lankan performers, which were staged in the Netherlands between 1902 and 1909 (TEYE1014541- TEYE001014554, TEY001014511 – TEY001014518, TEY001014519 – TEY001014528).

In South India, Hagenbeck recruited animal trainers, acrobats and magicians, bringing Oriental fantasies to life. The publicity material included images of bayadères or female temple dancers (TEY0010000098, TEY0010001959). Hagenbeck catered to a long-standing fascination for these temple dancers. Goethe had written a poem on Der Gott und die Bajadere (1797), and she was often cast as the lead in Romantic ballets, in which she was presented as a humble female. In reality, however, female dancers were associated with courts and temples in pre-colonial India, where they were esteemed because of their artistry.

The expansion of the British Raj, which involved the annexation of local principalities, signalled the end of Indian patronage of the arts, and female dancers slowly lost their status. Participating in human zoos may have provided a temporary solution to their inevitable marginalisation.

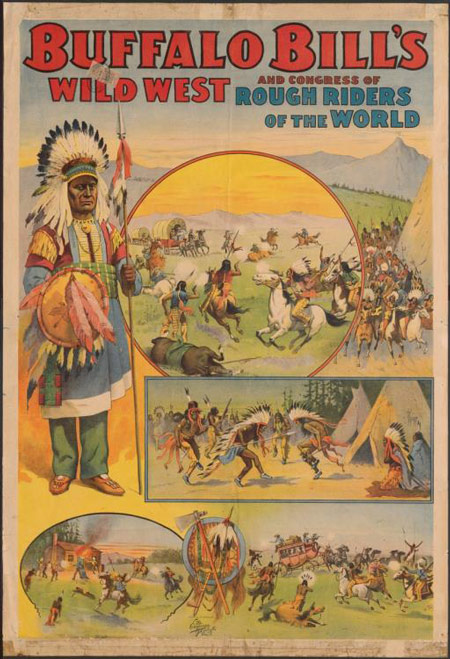

Wild West Shows

From 1884 to 1919, Germany was a colonial empire. Before and after this period, the country was in the grip of ‘colonial fever’, which also expressed itself in a sense of commitment to the native Americans. Not only did the German population admire their resistance against the colonization of the western United States, there was also the conviction that Germany itself would be a beneficent colonizer.

The European tours of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows (1897-1906 ) drew crowds everywhere (TEY001014145, TEY001014146, TEY001015480 to TEY001015495). Hagenbeck’s answer, with more than forty Lakota performers (1910), attracted more than a million visitors (TEY0010002264, TEY0010002978). In the wake of this success, Circus Sarrasani brought a performance troupe to Germany in 1913 (TEY0010003391), becoming the largest European employer of Lakotas after WW I.

The Lakotas were recruited in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (TEY001015905 – TEY001015907, TEY001014324). The American policy of assimilation entailed forced migration to the reservation, where they had to accept an agrarian existence, while their religious rites and traditions were suppressed. Touring Europe offered an income and initially provided a platform to share their traditions as well as their fate with the world.

For more information:

Hanke, Sabine. 2020. National identity and cultural difference in the British and German circus, 1920-1945 (PhD thesis, University of Sheffield).

Rothfels, Nigel. 2002. Savages and beasts. The birth of the modern zoo (Baltimore; London: The Johns Hopkins University Press).

Thode-Arora, Hilke. 1989. Für fünfzig Pfennig um die Welt: die Hagenbeckschen Völkerschauen (Frankfurt; New York: Campus Verlag).